Our director, Levent Kerimol, takes a look at ‘A House for Artists’ from a community led housing perspective.

‘A House for Artists’ has had a lot of coverage, especially now that it is nominated for the RIBA Stirling Prize and many other awards. My relationship with the project goes back to a brief meeting with Create, then an East London arts organisation, to discuss the concept, shortly before I left the GLA. I’ve watched the project from afar since. It is hard enough to build anything, let alone a scheme that unlocks possibilities for what our housing might be. I’ve heard ‘A House for Artists’ discussed as though it may be community led housing, so I was keen to visit for myself. I was lucky enough to be shown around by Nicholas Lobo Brennan from Apparata architects, albeit briefly, a few weeks ago.

Firstly, to get some things out of the way, the fact that artists are supposed to contribute in-kind work in exchange for reduced rent seems the least convincing part of the concept. There is no doubt artists on lower incomes need affordable housing, but so do many others doing similarly valuable work. Affordable intermediate rented housing should be available to any household on an eligible income, wherever they work.

Secondly, community led housing should not be misunderstood as housing for particular demographic communities. There may be a logic in linking ground floor workspace with artists, and certain people may value having neighbours that share similar life experiences, but neighbourly mutual support can emerge in all sorts of mixed communities. So let’s not dwell on the artists, and consider the possibilities this project presents for anyone with an intention to live in a neighbourly way – something the vast majority of us are interested in.

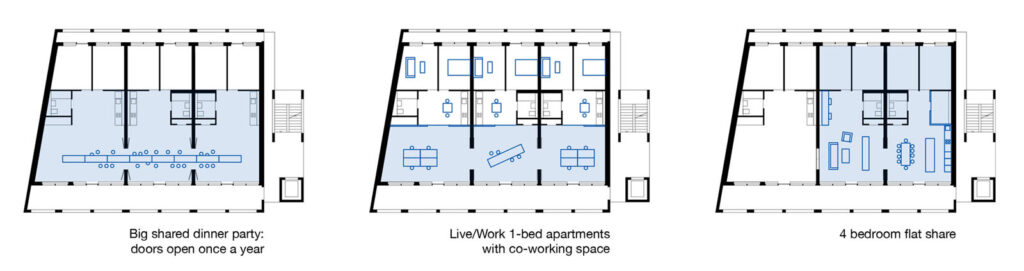

The literature suggests an element of “cohousing” in the scheme because three adjacent flats have double doors in the partition walls that can be opened to connect the living spaces into a single large space. This creates something like the cluster flats we’ve seen in German and Swiss Housing Co-ops. Closed doors are acoustically separated, meaning these work as conventional flats, unless there is a mutual agreement and strong desire to live in this way. Artists may be predisposed to alternative forms of living, but I didn’t get a sense this would really be put into use, except for the one night a joint party with lots of guests takes place.

That said, there was lots of scope for neighbourly interaction in the wide balcony walkways and large three-quarter height windows opening on hot days. Cohousing isn’t so much about sharing spaces within individual flats but forming connections across shared outdoor spaces. Nicholas told me residents often sit outside and eat together on these shared walkways. This is made possible with a very deliberate and carefully considered fire strategy, which Nicholas went into some detail about. The plan also allows residents to add internal walls and reconfigure their homes themselves.

The most interesting thing here is that the design goes to great lengths to make these community aspirations compatible with conventional housing. There are a few moments of subtle generosity, as much to do with what is not built, as what is. These tweaks make a radical difference, without an additional construction price tag.

The project was developed by LB Barking & Dagenham’s Be First company, for whom this transferability to conventional housing would have been important, so as not to be left with a white elephant if the particular uses fall away. Community led housing doesn’t have to be initiated or delivered by the community, but bringing some residents into the process earlier is important to kick-starting a community culture and a sense of belonging.

The selection of residents appears to have unintentionally thrown up such opportunities. Whilst there was the usual churn with some having to drop out during the process, prospective residents were able to meet each other and begin to forge a community before moving in, which rarely happens in conventional developments.

The ‘artist’ criteria in the allocation policy will be of note to several community led housing groups. However, I didn’t get a sense that residents have a say over whether they’re likely to get on with any new neighbours, regardless of whether they happen to be artists or not. This is frequently an ambition of cohousing communities.

More significantly, the ownership of the block itself sits with Reside, another LB Barking & Dagenham company set up to provide intermediate and market rented housing. Residents have little influence over their landlord, which they would in community led housing. True cohousing would have seen ownership, or even management and maintenance, transferred to a co-operative of resident-members, for example.

The thought of maintaining your housing block is not a task many will relish. It seems much easier to leave it to others. Yet we all care if repairs are not done quickly and effectively, or if cleaning is poor or costs too much. These are some of the things that matter most to people in their homes, and having the ability to influence them is important. Even if residents are not directly delivering these services, simply being in a position to change things is empowering.

My emerging hypothesis is that the responsibility and obligation to participate in what appear to be banal management decisions, are actually what binds a community together in the long term. It means neighbours have to meet regularly and work together to reach agreement. This leads to the sociable, neighbourly, mutually supportive communities we all want to see, almost as a by-product.

The question is how extensive do these management responsibilities have to be? If we go back to the activities on the ground floor, the fact that residents are responsible for programming the use of the space, and have to decide on this together, may give them a similar common responsibility over an aspect of the building.

A common activity naturally brings people together. Coupled with having things in common as artists, being part of a unique project, and a design that lends itself to community interaction, may well be enough to make ‘A House for Artists’ feel a lot like community led housing or cohousing. It will be interesting to see how long this sense of belonging persists into the future and whether a community culture is reinforced and reformed as future generations of residents come through the scheme, without real ownership or control by residents.

I didn’t get to speak to residents and the experience of home is very personal and will differ from my reflections. However, looking at this project gives us some of the elements that might be needed to infuse community led approaches into conventional housing development, even if some elements were unintentional or missed altogether.

This promises to be an exciting area for community led housing in the future, and could be considered a limited example of our Build Belonging approach.